Main Results

Percentage Point Changes in Probability of Field Choice

Multinational Presence Shapes College Major Choice

November 24, 2025

Lower- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) have seen an increasing rate of fdi inflow in recent decades

Source: World Bank

Tertiary enrollment rates have increased in LMICs

Source: World Bank

Hypothesis: Multinational Firms affect skill specialization decisions

Identification Strategy

Mechanism of fdi shifting human capital specialization decisions

Determinants of College Major Choice

Effects of increased trade/fdi inflow on local labor markets

Mechanism of fdi shifting human capital specialization decisions

Determinants of College Major Choice

Effects of increased trade/fdi inflow on local labor markets

Mechanism of fdi shifting human capital specialization decisions

Determinants of College Major Choice

Effects of increased trade/fdi inflow on local labor markets

Education

Public universities require applicants to list their two preferred majors when applying Example

Multinational Firms

Costa Rica incentivizes FDI inflows through dedicated Free Trade Zone (FTZ) regime

Major Choice Data

STEM & Applied Sciences

Soc. Sci. & Prof. Studies

Arts, Writing, & Service

Multinational Firms

Individuals Utility from Studying in Field of Study (m) is:

\[\begin{equation} U_{idmt} = \beta_{m} \Gamma_{djt} + \gamma_{i}X^{'}_{i} + \alpha_{c} + \alpha_{t} + \varepsilon_{idmt} \end{equation}\]

Subscripts

\(i =\) individual, \(\; d =\) district-of-residence, \(\; m =\) field of study, \(\; j =\) industry, \(\; c =\) canton, \(\; t =\) year

\[\begin{align} \Gamma_{djt} = p_{mjt} \times \left(\sum_{d'}\sum_{j} \dfrac{\text{Tenure}_{k(j),d't}}{exp(\text{dist}_{dd'})} \right) \end{align}\]

Subscripts

\(d =\) district-of-residence, \(\; d' =\) district-of-operation, \(\; k(j) =\) firm \(\,k \,\) in industry \(\, j\), \(\; t =\) year

\(\text{Tenure}_{k(j),d't}\): Tenure of firm captures how long individual has been aware/exposed to presence of MNC

\(exp(\text{dist}_{dd'})\): Distance (in km) from student-district to firm-district

\(p_{mjt}\): Industry Attachment Probabilities

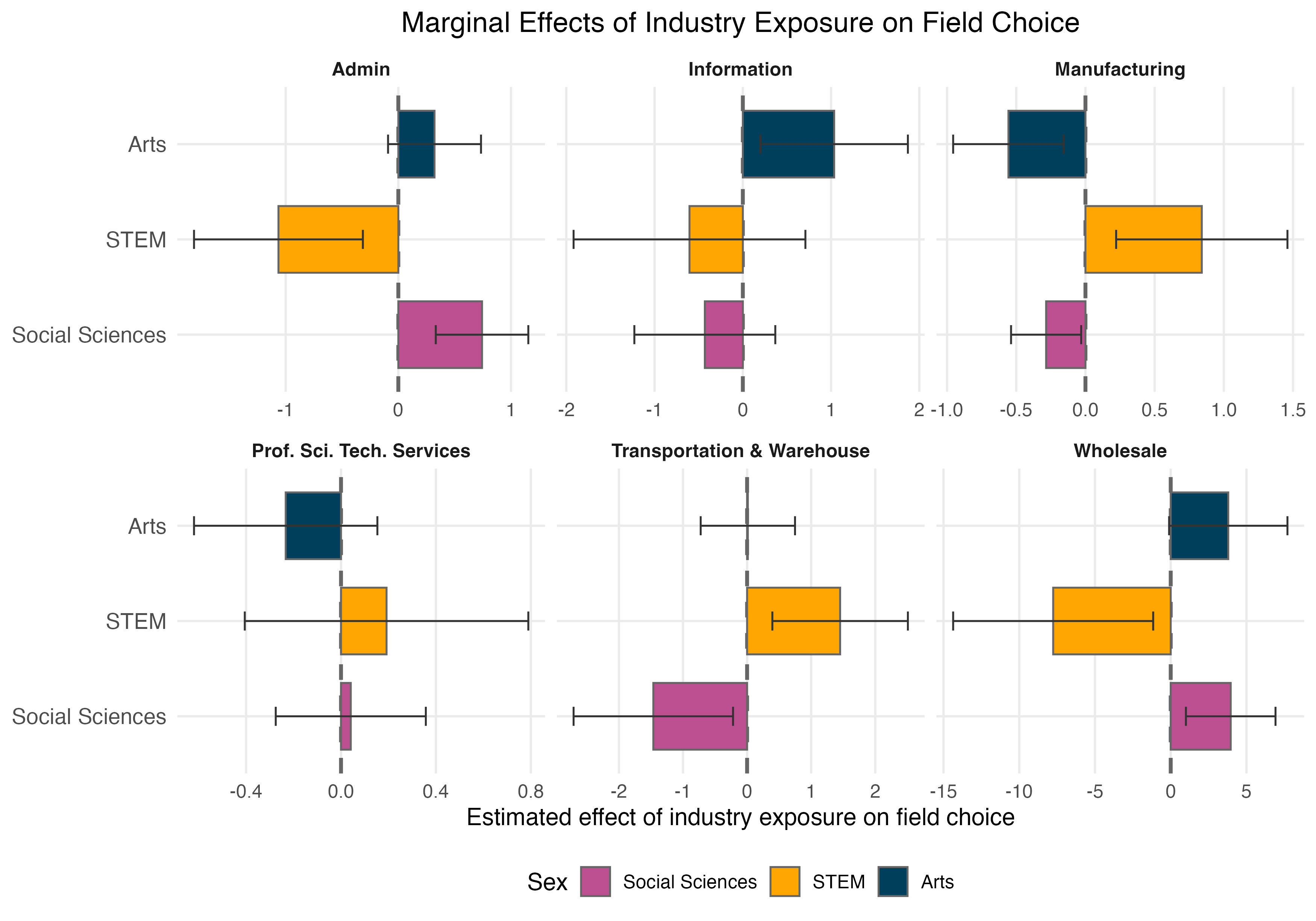

Estimate the effect of MNC presence on student field of study choice by using a Multinomial Logit Model and then estimating the Average Marginal Effects (AMEs) for each industry

This produces estimates that tell us how much the probability of choosing a particular major changes when the MNC Presence Index increases by one unit

Interpretation

In this model, this is interpreted as an additional firm-year in the student’s district of residence, which is either a new firm entering or an existing firm maturing

I also report the distance decay of the effects, showing how distance diminishes the presence effects

I then report results by exposure level differences

Percentage Point Changes in Probability of Field Choice

Percentage Point Changes in Probability of Field Choice

Trends remain largely similar across industry and field with significantly small coefficients

Multinational Presence Shapes College Major Choice